Working in the world of movement and manual therapy is a privilege. It gives me the skills and tools to help people strengthen their bodies and facilitate healing or soothe and comfort them, and I also have the opportunity to educate people.

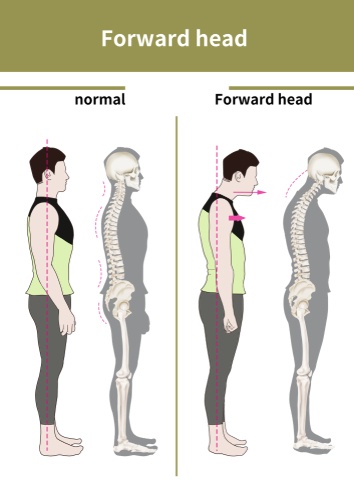

I have this posture. Many of my clients have this posture, where the head sits forward, accompanied by rounded shoulders and some upper back flexion. It does not impact some people, even with a marked FHP; on others, with only a slight postural dysfunction, it can make them dizzy or have headaches. In clinical practice, I see many clients with headaches, neck pain, TMJ problems and episodes of dizziness and balance problems. I talk about FHP and as you can see the rest of the body will adapt and accommodate this.

Neck pain is a common complaint in people with FHP, especially adults and older adults. There is strong evidence to suggest neck pain is more common in women. A research study 2019 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-019-09594-y) found that adults with neck pain show increased forward head posture.

Forward head posture also affects our balance and postural control. According to a systematic review it carried out in 2022 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.10.008). The significance is that forward head posture has a detrimental effect on postural stability, performance-based balance and cervical proprioception. Although the research on gait disorders was conducted on children with FHP, it is plausible to hypothesise that they are associated with FHP.

There is a higher risk of falls in older adults. A study carried out in 2019 on young adults with forward head posture concluded that individuals with FHP showed decreased balancing ability and increased reaction time. We can hypothesise that to work on improving upper body posture and awareness in older adults then, balance will improve, and so will reaction time.

It seems a misnomer to say that neck flexion may facilitate forward head posture when what we see in every picture depicting this image also shows thoracic kyphosis.

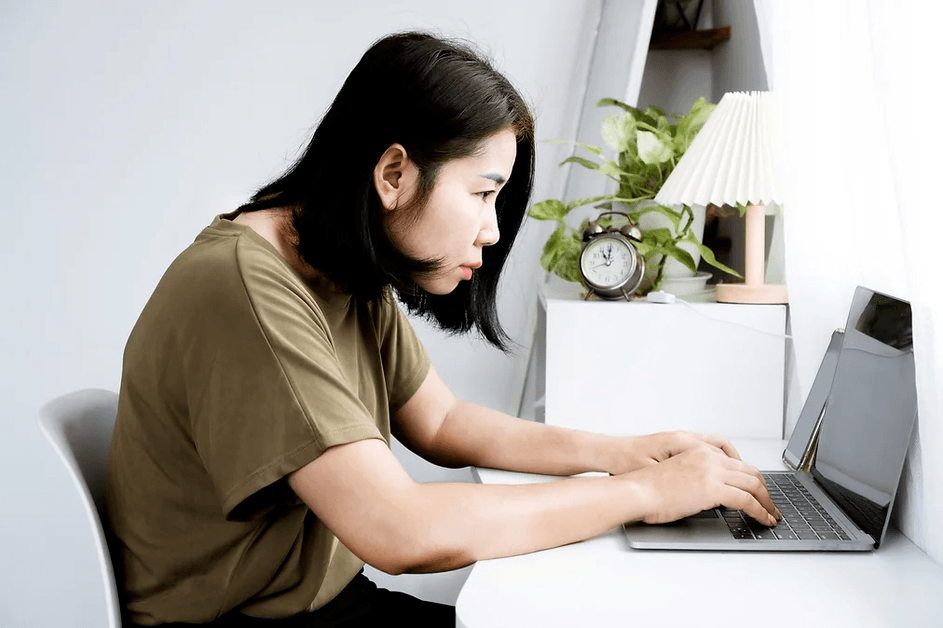

The head can move independently of the spine, and the head may also adapt to a new position because of the spine. The image above is a very common position for many of us and one we will explore in a moment. And then what if we go to the gym or an exercise session and we are asked to keep our head up? what exactly does that mean to you? Or to keep your eyes to the ceiling or your head back?

Try this:

-

Sit at your desk or the table.

-

Drop the head a little; this is neck flexion. You can feel a stretchy feeling at the back of the neck. Some of you will already notice you have slumped a bit. Some forward flexion of the spine. You may even notice that the shoulders have rounded or you feel the shoulder blades have moved apart.

-

Imagine you want to look at your screen or speak to someone opposite. You have choices: a) sit tall and return the head to start. b) you bring the chin up and tilt the head back. Almost all of you will pick b. The body is capable of doing those movements. The problem is when we keep doing it or stay there for long periods, and the position becomes our default, our new normal.

-

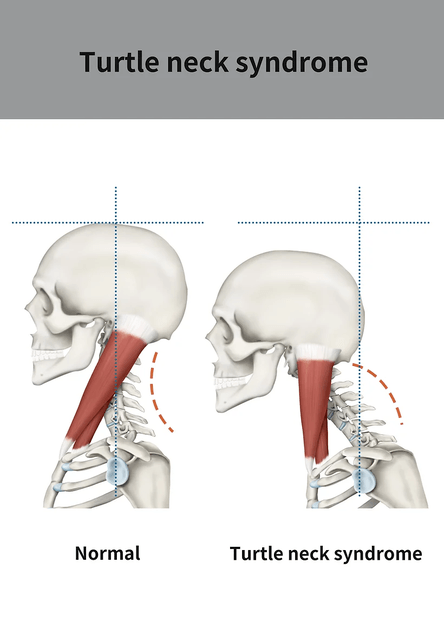

We are now slumped with our heads tilted back. We stay here for a while, and most of you will notice the head gets heavy, and you relax. As you settle into this position, the spine, shoulders, and head go with you—positional shortening. The body adapts to the demands placed on it. The deep neck extensors shorten, as do the chest muscles. The deep neck flexors weaken.

-

Structural and functional changes take place.

-

So if we are going to correct our FHP, we need to be aware of more than our head. As we retract, draw our chin in, we lift the head and eyes to orient with the horizon. We should bring our breastbone up and lengthen our spine to soften and adjust the curves.

-

As you carry on reading or take a moment to look at the images, you may feel different areas of the body taking on a new position or different sensations in the muscles as they get a bit of a stretch or engage. You can try and find the best position as in the earlier image, you might notice you are working very hard to try and maintain this. I would encourage you to soften this to an effort that is about a quarter to a third of that maximum effort, and then try and keep this as you sit at your computer or go through a couple of exercises.

This next bit is for anyone treating or teaching and clients that are just interested in more.

Words don’t come easy, as the song goes. Therefore, words are potent, and we must choose them carefully. As a movement practitioner, it is not enough to say keep the head up or keep the head back. As therapists, we must remember and convey one part of the body’s relationships with another to our clients.

In a beginner session or a session where I want to bring more attention to the position of the head during exercise and ultimately to active daily living, I start with what is neutral. We discuss the ideal place and then what is suitable for each person. We want to be able to move the head and stabilise the head. FHP very often leads to a stiff neck and reduced range of movement. I always teach head and neck posture in all exercise start positions as it feels different from four-point kneeling to supine. I want people to learn to engage the deep neck flexors of longus capitus and colli to help strengthen them to help align the head. Slow and gentle improvements win every time. We have layers of muscles, we may need to lengthen some of the bigger and stronger superficial muscles and strengthen some of the deeper muscles.

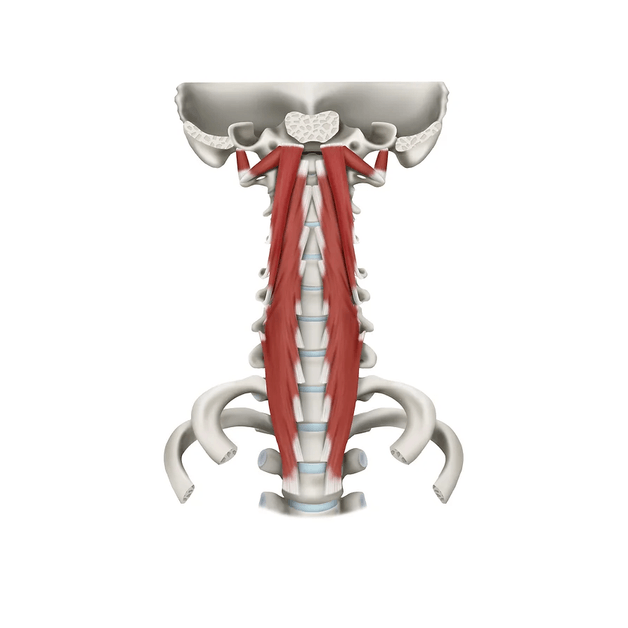

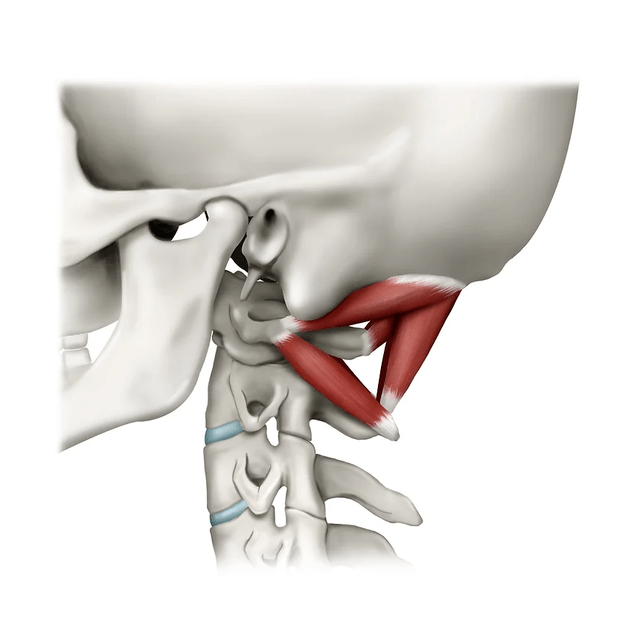

The suboccipital are four small muscles at the back of the head that fine-tune and stabilise the head position. They might be small and play an important role in proprioception and feedback. These muscles are highly innervated with many mechanoreceptors. They are susceptible to fatigue. In neutral EMG activity of Rectus Capitus Posterior Major and minor was around 10%-18% the maximum voluntary isometric contraction; this increased to about 34%-42% MVIC with FHP. All muscles surrounding the cervical spine structurally adapt with function altered over time. The suboccipital muscles have a connection to the dura via myodural bridges. The length-tension relationship transmitting forces offer stability to the spinal cord, and the feedback may help maintain the integrity of subarachnoid space. If the length-tension relationship is balanced, the sub-occipitals may work as a pump via the bridge for cerebrospinal fluid circulation.

Please read the following research article to look at the suboccipital muscles and forward head posture in more detail.

Suboccipital Muscles, Forward Head Posture, and Cervicogenic Dizziness – Published Dec 2022 – doi: 10.3390/medicina58121791